Our hope is to create a tiny moment of visibility for what was and for what could be once again.

We wanted to participate in the discourse regarding the privatization of public spaces, through reminding people of a less segregated and gated past.

For our public intervention, we first went to a squatting protest at the Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal, where four squatters were evicted by a judge last Thursday. The building belongs to a well-known owner of Amsterdam buildings, who renovates and then sells the buildings he acquires. This building was also to be renovated and apparently the squatters were blocking that renovation, which led to their eviction.

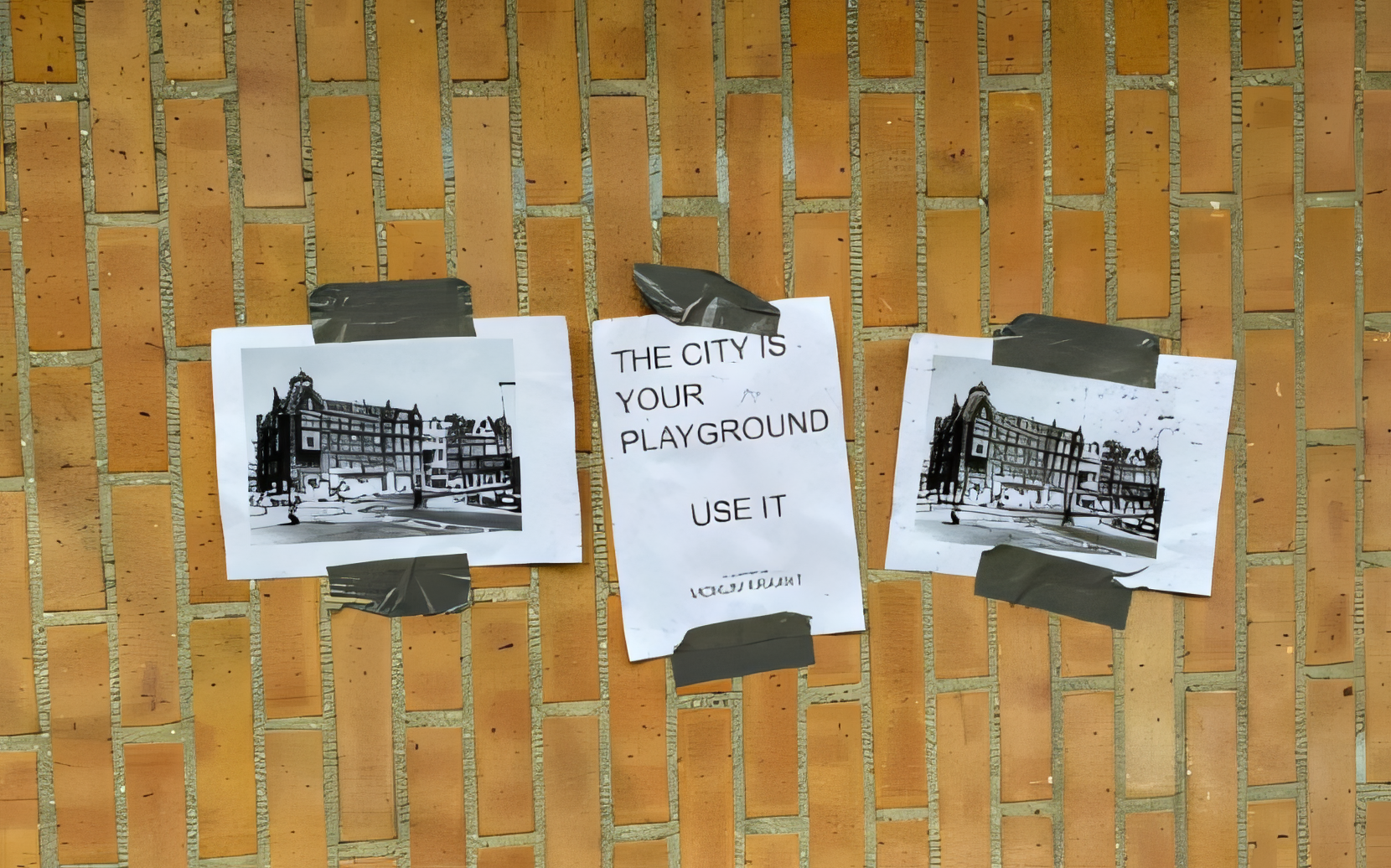

The organizers of the protest explained that protesting the urban policy in Amsterdam does not only have to occur through actual squatting, but can consist of many more, smaller and larger actions, which are founded on making visible what is now often invisible, such as homelessness, housing shortage, private ownership taking over the city, etc. This concept of (in)visibility inspired us to shine a light on the past of the city that was now obscured. Hence, we printed images of once squatted buildings that were taken down, in the places of which now stood privately owned buildings. We wanted to make visible what was there before, and perhaps also what could be there again if policies change, which is why we decided to stick the images to the actual buildings. Even though our images are just paper posters that have probably already been ruined by the rain, we hoped to, even only temporarily, to contribute to the visibility of the dynamics of ownership as a dominant discourse in this city. We accompanied these images with a quote from the speech from the Mokum Kraakt organization (the organizers of the protest): “the city is your playground – use it”, which refers to the many ways in which it is possible to interfere into these kinds of dominant discourses.

We have chosen three buildings: one in the Spuistraat, one in our university street, and the last one being the Jan Luijkenstraat number three. The latter was built at the beginning of the twentieth century and is a national monument for its architectural style. In the seventies it was bought by a notary who became famous because of fraudulent practices. As a consequence, the tenants could no longer afford the rent, the building became empty and it was intended to have it auctioned. But the building remained empty and then squatters moved into the building. They were eventually violently evicted by the police, which led to one of the biggest confrontations between the police and the squatting movement in the Netherlands. After the eviction, the building was used for social housing until 2014, after which the apartments became free sector rentals. Thus, the buildings became only accessible to those with high incomes. This story highlights many issues at stake for the squatting movement: the dynamic of ownership vs. housing rights, but also the apparent opposition between private and public space. The right to a house implies the right to a private space, which is important to every human being, yet the privatization of the city is leading to a decrease in public spaces. This building was, when the squatters moved into it, public in a way: there were no rules for who could live there or not. Now, it is just another building available to high income people in a neighborhood dominated by high incomes.

The city’s fabric, as squatting organizations often argue, is less and less made up of actual people living actual lives, and more and more of ownership, real estate, and capitalism. This dominant influence of ownership, profit incentives, and capitalism is literally taking up space in the city. The acquisition, renovation, and marketing of buildings that used to be lived in, or used as public, communal spaces is transforming the city. Instead of giving back these spaces to the city – not even as housing but perhaps as a communal neighborhood space where children can play and adults can have coffee together – these buildings are, as remarked at the protest, often passed down in families, often from father to son. In this way, this trend also embodies and exposes the patriarchal nature of the structures of capitalism. Our choice of form for a public intervention is relatively low impact, but our hope is to create a tiny moment of visibility for what was and for what could be once again, reminding people that things have not always been this way – and therefore, don’t always have to remain this way. Thus, with our intervention we have hoped to slightly amplify the squatting movement’s message, by adding our own tiny sentence to the story of the city.

Some info on squats in Amsterdam:

Mokum Kraakt

https://www.instagram.com/mokumkraakt/?hl=en

Squatnet

Joe’s garage, Pretoriusstraat 43

https://radar.squat.net/en/amsterdam/joes-garage

De Nieuwe Anita, Frederik Hendrikstraat 111

Vossiusstraat 16, building owned by Russian billionaire turned into a squat