Take a bit of Amsterdam home with you, have more space next time you visit. Help us make Amsterdam more tourist-friendly!

“ (…) with a humorous and critical tone, we aimed at questioning and discussing the consumption-oriented and gentrified structuring of the city and the municipal policies’ capacity in addressing the increasing commodification of public spaces.”

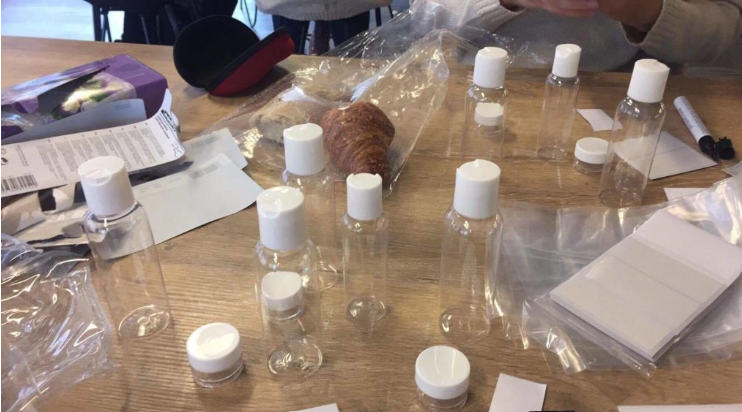

Rebuilding Singelgracht public intervention is based on interacting with tourists in Amsterdam to introduce them to the so-called “Rebuilding Singelgracht Project” designed by the municipality, which aims to optimize Amsterdam for the growing flow of tourists. We approached tourists by pretending that we were municipality officials who gave them information on the project. The project is described as follows in the flyers we distributed: “The project changes parts of the city from 17th century infrastructure to modern and vibrant shopping streets. The renewal means more space for tourists and more space to enjoy Amsterdam. With this project, the canal will be drained, filled and rebuilt into the new Singelgracht, which will transform the canal into a street.” The tourists are asked their opinion and given a small bottle filled with canal water as a souvenir. During the intervention, various conversations are held with the tourists and passersby about the current conditions of the city, the increasing number of tourists in Amsterdam, the gentrification of the city and possible urban policies that deal with or fall short in tackling these issues. These conversations, with a humorous and critical tone, aim at questioning and discussing the consumption-oriented and gentrified structuring of the city and the municipal policies’ capacity in addressing the increasing commodification of public spaces.

The intervention was inspired and shaped by the Situationist International’s urban theories (“Formulary for a New Urbanism”, “Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography”, “Proposals for Really Improving the City of Paris”) and the concepts they have developed in their writings, such as “psychogeography” and “detournement” (in Ken Knabb, Situationist International Anthology, 2006). Translating these theories into the contemporary urban setting has allowed us to revisit and reevaluate the theories and concepts themselves, shedding light on their efficacy and explanatory power today. We recorded the conversations by getting permission from the people we interacted with, photographed the objects we used (such as the small bottles filled with canal water and the distributed flyer) and presented our theoretical and practical conclusions.