We asked ourselves: how can we begin to consider the history of politics (and the politics of history) as a way of maintaining cultural and symbolic significance?

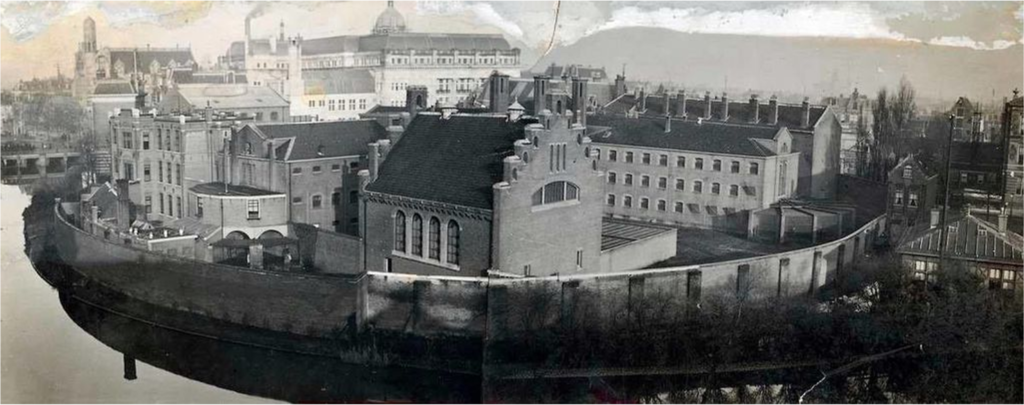

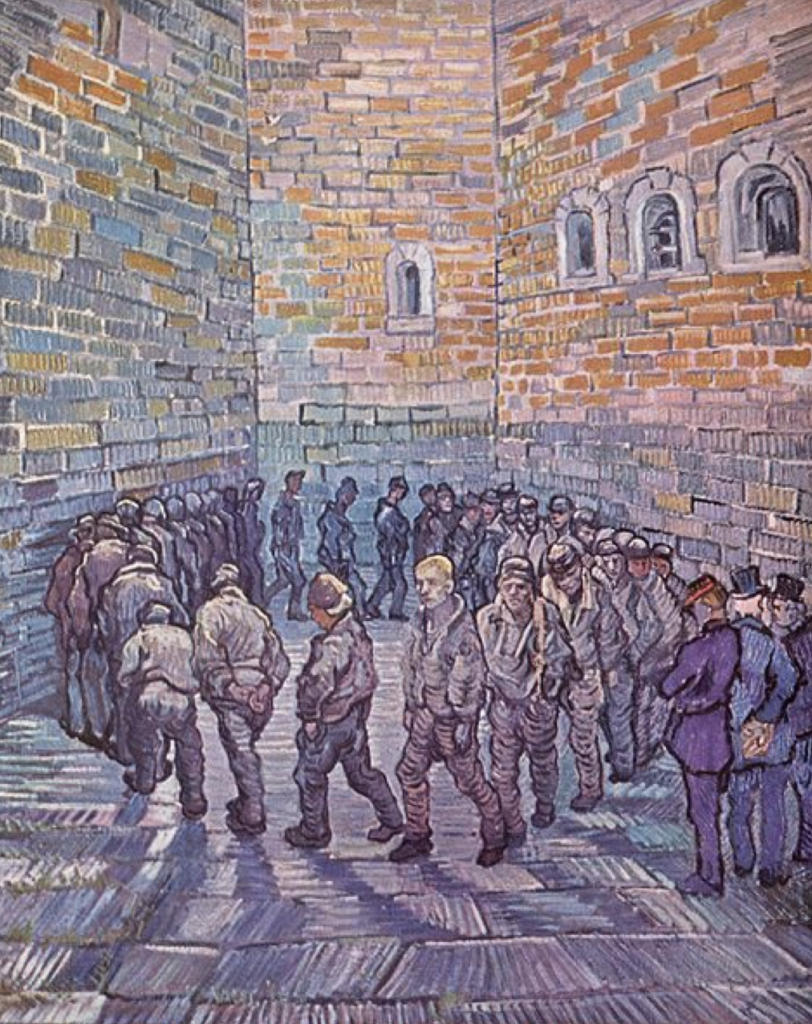

We chose to analyze the significance of Max Euweplein, in relation to the city’s ‘cultural archive’. This square proved very insightful to our intervention, as the main building crossing the square was the first prison built in Amsterdam, in 1850. The building was then used as ‘waiting rooms’ for Jews during the Nazi occupation of Holland, in which prisoners were made to walk around the square saying “I’m Jewish, it’s all my fault, please beat me.” We wished to highlight the historical significance of the square, by asking random passersby to accompany us on a circular walk around Max Euweplein – and then (with great pleasure) explain the rather dark history of the square. People were asked to take a walk around the square by following the circular route the prisoners once used to pace back and forth. The performance, which the passersby become part of by strolling around in the now highly touristic area full of cafés and bars, attempted to reveal hidden layers of history in the city for its inhabitants.

We encountered five different groups of people (although the demographic was targeted: English speakers, no children and open-minded looking), each group was more surprised than the last (with the exception of elderly Dutch couple we spoke to, because they knew a little about the city’s archive.). Nobody knew the significance of the square, or even realized it used to be a prison – safe to say our demographic were surprised to say the least. It was difficult to convince a few groups to join us on the walk, although those that were willing to participate were shocked by the history of the square.

We chose this square in particular because it’s a location that many people frequently cross and pass over, without considering the cultural archive that remains hidden in Max Euweplein. All in all, we surprised the public by revealing hidden pockets of history to our unsuspecting victims. It was a topic of a rather distraught nature, yet we managed to surprise (almost) everyone.

We asked ourselves: how can we begin to consider the history of politics (and the politics of history) as a way of maintaining cultural and symbolic significance? In this way, the Holocaust serves as a ‘glitch’ in our public intervention: demonstrating how indeed politics acts as a stabilizer on Max Euweplein; yet simultaneously rupturing Amsterdam’s archive by revealing what was previously unseen.

The intervention is inspired by Denis Cosgrove’s seminal text “Geography is Everywhere: Culture and Symbolism in Human Landscapes” from (Horizons in Human Geography, 1988), in which Cosgrove argues that landscapes carry symbolic meanings that can be read as “texts”. Another theoretical inspiration for the intervention was Lauren Berlant’s The Commons: Infrastructures for Troubling Times (2016), which is used to discuss the ways in which infrastructures of the past inform or mystified by the present infrastructures and what an awareness of the interaction of multiple infrastructures in the city can lead to.